Technologies of the Picturesque

Maps, clouds, and cattle. Technologies of the Picturesque begins with the deceivingly simple premise that these common objects of earth and sky can be used to understand Romantic landscape poetry and painting. While material objects themselves remain enigmatically mute, as they get deployed by technology and aesthetics, these objects speak to humans. Likewise they speak of the human. They serve as examples of how nature gets transformed through political, historical, and artistic investment.

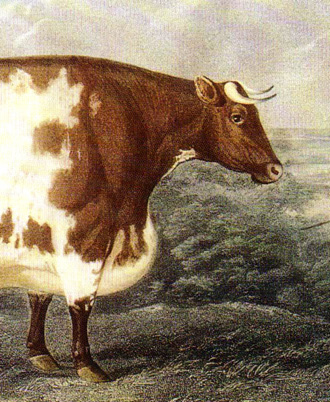

Portraits of cattle popularize the new method of animal husbandry. These portraits borrow from the techniques of traditional picturesque painting in order to naturalize the improved animals. Conversely, the picturesque gets recoded as cattle take on meaning not as bucolic beasts but as an improved national agricultural resource.

In 1821 Constable began painting clouds with a sensitivity to meteorological changes and his clouds serve as a response to problems in taxonomical mapping and naming of the protean white forms. In contrast to the Romantic period classification of clouds (which we still use today), Constable renders the passing duration of clouds such that nature's temporality precedes and even supersedes human spatial systems. In Constable's paintings the viewer witnesses the weight of time upon the landscape.

The century-long project of Britain's first National Ordinance Survey influences the picturesque aesthetic. Lines of sight, station points for observation, framing of scenes, and privileged high vantage points for viewing used by surveyors change picturesque modes of seeing and representing nature. The viewing subject becomes rationally abstracted from the place and is increasingly isolated and decorporealized.

In contrast, an extended look at Wordsworth's densely entangled landscapes reveals characters who lose their way only to reorient themselves not from a prospect view but through contact and association with elements within the land.